One of the last living historians of Chicago, Timuel Black, is no longer living among us. On October 13, 2021, he passed away at the age of 102. He published two volumes of oral histories, Bridges of Memory, which remain an essential people’s history of Chicago. When I was working on my book The Negro in Illinois: The WPA Papers, I had the chance to sit down with him. I interviewed Mr. Black on May 10, 2011 at his apartment in Hyde Park. On the occasion of his passing, I’m publishing the transcript where he reminisces about those he knew like Margaret Burroughs, Charles White, and Ishmael Flory. My heart goes out to Mr. Black’s wife and family.

Timuel Black: Most of the people that came to Chicago before world war one and between and World War I and World War II, those were not necessarily academically trained, but they had industrial skills like my father. Most of the people came roughly between 1915 and 1950 came from urban areas of the South. They had lived in the rural South. They had been sharecroppers, many of them, like my mother and father. Their parents were former slaves. But they could read, write, and count in the urban areas of the South. In the terror of the South of that period, that so many of them were lynched, abused. When the word got out, and that was primarily because the industrialists and the manufactures were trying break the developing union movement. Immigrants from Europe had learned how organize as they became industrialized earlier in America. They learned how to organize and they brought their skills with them, though they couldn’t speak good English yet. They were needed. The owners of those big businesses sent agents to the South to recruit the children of former slaves assuming they would be cheap labor. The unfortunate thing was that those who were doing the organizing had strong racial feelings about these newcomers and they weren’t going to let them join the union. My daddy, like many, couldn’t join the union, but he had to feed his family.

Robert Abbott, the founder of the Chicago Defender, sent his papers south by railroad porters. They’d leave them at the station and someone would pick those papers up and distribute them. The paper would get read three, four, five times. People in the South couldn’t believe what they were seeing about, “Come North Young Man,” this is what the difference would be, they couldn’t believe that. Then, of course, when they came here they found out he wasn’t completely accurate. But they could send their children to school, like my brother, my sister, and I. Most of the people in my generation, who came at that period of time, graduated from high school, 85-90 percent of them. They either went to college or went into business. This funeral I went to today, the people there with children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, they bragged about which college their kids went to. It wasn’t a matter of did they go. They would say “Which one?” Like I can brag about my son going to Stanford, or my daughter going to Bennington and then Northwestern. Which hurt, in a sense, the historically Black colleges and universities like Howard, Fisk, or Morehouse.

The point is that they came and formed, because of the segregation, parallel institutions in the neighborhoods, the ghettos, where they were confined to. My daddy and his friends, they could work outside because they were needed, but they could not have their families living outside, nor could they spend their money outside. So the money came into our community. Our business minded people started business like the funeral business, like buying cemeteries. We didn’t have any taxis we could use so Jackie Reynolds created the “jitney” taxi, and others like him. Banks wouldn’t lend folks any money, so Jesse Binga and others created the banks in the community. The numbers business, the “policy business” as they called it. The Jones brothers were educated in Mississippi, they saw an opportunity to become multimillions. The first ten Black certified public accountants in the country came out of Chicago in that period because there were businesses which could give them the jobs and the money. We weren’t rich but we had models in the same neighborhood.

My father worked in the stockyards and steel mills, but down the street there were doctors, lawyers, school teachers and all. The kids at the playground. I played with Julian Dawson. Dawson had to play with me. I could play better basketball than him, but he had the money to afford the basketball, and we had a good time. A generation later, and this is typical, this is not untypical, when I’m teaching high school I had Julian Dawson’s kids as my students. They would go back and tell their daddy, and he could say “Yeah, we grew up together.” There was a continuity and a kind of positive attitude about the future that existed in my generation and the generation of my children.

The second Great Migration that comes after World War II, they didn’t flee the South. The new agricultural technology pushed them off the land. They were not urban. If you listen to the blues you’ll hear the difference between the country blues and the city blues. One is cerebral and the other is visceral. Those of us who grew up on city blues, we’re snobbish about country blues, although that’s where most of the money was made.

That’s a little bit of the history. Out of that emerged a lot of artistic talent, both in music, in paintings, and in writing. To some extent, Arna Bontemps is a product of that earlier period. But even later you get Margaret Burroughs. You get my late childhood friend Charles White. You get Marie Bryant, who was the choreographer for Duke Ellington. On and on and on. And then you get the John H. Johnsons of the publishing industry.

BD: These are very important figures. Margaret Burroughs is a giant to me. Charles White is a master. So what can you tell me about those two people?

Margaret came a little later. In elementary school, we went to Edmund Burke School together, Charles and I. I just mention him as one person, but there were quite a few others. We knew early on that he was a gifted guy. Even before he graduated from grammar school, the Art Institute of Chicago, learning about this young man, would come and help him put up exhibits in our hallways. Then when he left elementary school and he went to Englewood High School, which was where he met Margaret Burroughs. I went to Englewood shortly, but that’s another story of class, in a sense. That’s where he and Margaret met.

At the time, the Art Institute was searching for young, talented people like them, crossing the color line. And so they began to be nurtured by the Art Institute. Charles, because he went from there to New York, then he politically began to move to the Left. Of course, so did Margaret move to the Left, the way Left. His mother continued to live in the neighborhood until she died. He’d have to come back and see his mom in the “hoodlum” area, which was the term by that time. But she owned the building, I think.

BD: You mention the leftward turn of these figures. What was creating this? Obviously, it was the thirties. What specifically led to that leftward turn?

It was the Depression. In the early part of it, the artistic types, who were also intellectuals, Langston Hughes, all of those artists in New York. That period called the Harlem Renaissance―Chicago was having its own renaissance. There was an exchange between the New Yorkers and the Chicagoans. I wasn’t an artist, but I knew many of them.

We also had, I forget his name, who used to live right down the street. He wasn’t an artist, but he was an agitator. What was his name? In Washington Park, which right across the street from my elementary school, those guys―and Langston Hughes, and Du Bois, and Paul Robeson―they would come in. They had a forum called the Washington Park Forum. My daddy, though he didn’t go that far in school was a bright guy. Of course, at that point in the South, very seldom could anyone go beyond elementary school unless you lived in the urban areas. He read, my mother read. I didn’t know people who couldn’t read until I went to the Army. He was a Garveyite, my father was. Marcus Garvey, who was a Black nationalist. I’m trying to think of this guy’s name.

BD: Ishmael Flory?

Yes. They would be talking out in the park and people like my dad would take their children to listen to these men. The park was right behind Newberry Library, I think they called that Bughouse Square. They cross-pollinated in terms of creating interest among younger people, particularly. We would see that and the school that I went to, Edmund Burke School, was mixed racially in the beginning. You might see middle class-type Jewish people, middle-class type Irish. Just the name itself, Edmund Burke was an abolitionist.

That period, the Depression, hurt. There was no welfare. There was charity, but there was no organized welfare. No social security. None of those things that we take for granted today, but maybe we shouldn’t be taking for granted. If a person couldn’t pay their rent then they were put out on the street with no place to go, except to go sleep in the park. One of these older guys, Ish Flory, or another person, says Ms. Jones has just been put out, let’s got put her back. For us kids that was fun. We’d go put Ms. Jones back in. That was just fun. It was like playing a game. And yet psychologically we were beginning to admire these courageous men and women. This is where Charles White and Margaret got totally enmeshed. I didn’t. That didn’t mean I wasn’t affected in a different way. They really embraced these older, heroic people―who also were bright. They had these talents that they could transfer to other young people like themselves and bring them into the fold.

My brother and sister lived before the Depression, so they had a pretty good deal. The Depression hit me by the time I graduated. You may look in the book Bridges of Memory and you’ll see Bill Green, myself, and his mother in the book, who graduated from grammar school. Bill Green went on to be the first Black Internal Revenue agent in the country. Bill Green, and others like him, it didn’t bother, because his father worked at the post office. That was considered big time.

Since my parents didn’t have that kind of predictable income, I began to hang out with the tough guys. My brother’s already swanky. I’m not saying that in derogation. My brother’s a great guy. He’s the first Black captain of the basketball team at Tilden High School. Lou Boudreau tried to get him at the University of Illinois.

I began to hang with the tough guys, because I couldn’t show off my clothes like these others. It was competitive, for the girls and the boys, how you looked and where did you buy your suit. Well, I couldn’t compete with that. A small group of street guys, not like today’s gangs, just street guys, kind of tough, and they were fun, they were great. But they were great athletes. They could play baseball, football, and basketball. So I began to hang out with those kind. But to my brother’s friends, that was not a serious thing to be doing, you did that just for fun, and you did that in your spare time. Other time you spent reading books and talking about history and all that.

For me, that may have been an advantage because I got a chance to live in two worlds, which my brother and sister never had the chance. Fortunately, I never got into serious trouble because my hoodlum friends knew I was dumb and they wouldn’t let me get into trouble. I would come over to the University of Chicago and go to Rockefeller chapel and listen to the Black scholars, like Julian Bond’s father, who were going to the University of Chicago.

BD: Like Horace Cayton and St. Clair Drake?

St. Clair Drake comes later. Drake comes later. The writer, Richard Wright, they all come a little later. Yes, that’s the same time. Cayton and Drake were younger that Richard Wright. These were scholars who could not, at that time, get into Princeton and Yale, but they could go to schools in the South. They came to the University of Chicago, and places like that. The state would pay for them to go to the University of Illinois, University of Chicago, places like that, and the Mississippi, Georgia, wherever it might be.

BD: Arna Bontemps was a student at the University of Chicago as well. They were all, a number of, them graduate students there.

I would go over there and go to the chapel and then I’d come back to the pool room to tell my friends what I had just heard and seen. I was acceptable. And I could shoot a little pool. I wasn’t good, but I could shoot a little pool. But my brother, go into a pool room? I was very much like my daddy, my brother was much like my mother. Both were good people. My mother was more compromising and integrationist, a middle class attitude about money. Her attitude was, “We’re not going to live around these poor white folks,” even though we had a lower income.

What I’m describing is not untypical for the various levels of class in days of my years. After World War II, when Lorraine Hansberry’s father broke the second barrier in Shelley v. Kramer, guys like me returned from the service and started families. Already living with mom and dad, sometimes in crowded conditions, although at that time, my mother and father had a very lovely apartment, almost the size of this. Marrying a young lady, at the time the mother of my children, she wanted her own place. That was typical. We had the advantage of the GI Bill of Rights. To some extent we had better opportunities than those who didn’t have the GI Bill. That’s also true in education.

So we moved out of the old neighborhood after Shelley v. Kramer made restrictive covenants unenforceable anywhere in the country. I had been to Roosevelt University, and I moved over into Hyde Park with my family, although we moved out temporarily when I was working in Gary, Indiana. That solidarity, in terms of the diversity that had existed in the old, what Robert Abbott coined the “Black Belt,” which we now call Black Metropolis, or Bronzeville, we left en masse very quickly.

The newcomers coming from the rural agricultural South, with relatively few skills for the urban world, had been told that Chicago, or Pittsburgh, was the “Promised Land,” the “Land of hope.” When they came there were jobs initially, but those jobs went away, just as the jobs in the South. They had been denied the opportunity to have quality, decent education because they worked by the seasons―spring, fall, summer―they worked by the seasons. They’d better not go vote.

Whereas my father and his generation, that’s what they wanted to do. In fact, my dad would put his pistol in his pocket and go vote. He was considered crazy, because he had a sponsor, in a sense. Hugo Black, whose father was my grandfather on my father’s side slave master. Somehow, Hugo Black and my dad had communication even though Black was a Klansman. When he was nominated for the Supreme Court in 1937 by Roosevelt, I said Dad, you know he nominated a Klansman. My dad, who didn’t like white people in general said, “Oh, he’ll be alright.” I said to myself, my dad’s gone crazy. Black turned out to be one of the most liberal justices. He could not have gotten to where he was unless he promoted the Klan at that time. He couldn’t have gotten through the political mire of the South.

That break came and removed these newcomers, the jobs went away because the businesses began to move into the suburbs. Those of us who had left, our parents are now quite old, could not share with the newcomers the wisdom and experience that had been shared with us when we came in that period of time. They became isolated, schools began to deteriorate. Most of the people like me, and others, took their children out of those schools in those old neighborhoods and took them to better schools. Like my son, the group that grew up with him, most of them spoke at least two languages. They taught Spanish, French in the elementary school. Almost all had Latin. They had algebra in the elementary school. My parents pulled money together and those kids went to France and Spain even in elementary school. Parents like me and others demanded the teachers teach the children.

Even if children like my son and daughter wanted to go back in the old neighborhood, they were not welcome. That makes me know that Barack Obama did not go by himself out to Altgeld Gardens public housing, he had to have an escort. The escort may have been white, because they trusted the white guys more than they did us, because we thought we were smart. We acted like we were white at that time though. And then the gangs became to come in. Those young people’s parents took them out of the public schools altogether and sent them to private schools.

BD: If I can back pedal and take you back to the Depression. Tell me about Washington Park and its history. How did it change during the thirties and forties, fifties and sixties?

The breakthrough was the Hansberry case. Of course, you know Lorraine wrote her play [A Raisin in the Sun] based on Langston Hughes’ poem. With these newcomers losing their jobs, Washington park became more dangerous. We used to go out in the park day and night, didn’t make any difference. I’m not talking just because the park had air conditioning. We could sleep in the park with friends.

BD: Were Black folks allowed in other parks in Chicago?

No. Not in Jackson Park. Not in Lincoln Park. But Washington Park was our park at that time. So there was a lot of camaraderie in the park, and music, and you’d see Joe Louis running around the track, you’d see athletes that were famous already. Cab Calloway would come and his guys would play softball with us. The guys couldn’t play softball, but they could play music. They came out to have fun, and also to be big brothers. The Globetrotters. We learned how to play good basketball, but also how to be good salesmen. They’d come back and talk about the road, and how they had to make adjustments. Because the major thing was to play the game and win. Not to hurt a guy because you cussed him out, but you could make him feel bad because you beat him.

That period of the Depression had helped us learn how to make some social adjustments. Not just against the system, but with one another. Those who lived in the agricultural areas, of course they had things to eat and they thought we didn’t. But we did because Roosevelt then came. Herbert Hoover kept saying prosperity’s right around the corner. Well, we young folks looked around the corner, we didn’t see anything but soup lines. When Roosevelt brought in the New Deal, it had not just a Writers’ Project, but it had the CCC, the Civilian Conservation Corps. Those guys became so disciplined that when they were drafted in the army, they became noncommissioned officers almost right away. They knew the style and all.

Roosevelt took young people who were less fortunate in terms of income in the family. When the radicals, or the leftists, began to get together, that’s when Roosevelt inserted the Writers’ Project, which gave them something to do. They didn’t stop being radical, but they had something to do. They became better teachers. The Communist Party made more progress during the Depression in the United States than at any other time. Because they were dealing with needy people who also were intelligent. One of the parts of the New Deal was a youth project. My brother was a part of it. We couldn’t go to officer candidates school because we were considered too far to the Left, and that was across race lines.

And then of course World War II comes and jobs became more plentiful. With the passing of the Selective Service Act, all of us became eligible, from 18 to 38, to be drafted in the Army. A lot of guys, like a lot of my friends, who became Tuskegee Airmen, they wanted to be in combat, they wanted to be on the front lines. They were good Americans. They really wanted to be on the front lines. Now I didn’t. Oh, I found that I was a good American. They had a race riot in Detroit. Black males could not, even though they had relatives, I had an uncle and my cousins, they wouldn’t let you go up. My daddy because he knew I was like him. My brother was drafted, he knew how to make the adjustment. My daddy wasn’t afraid, so he said, “You don’t need to be going to Europe to fight, you can to Detroit and fight.”

When they sent me my first draft notice, “Greetings, you have been selected to serve by your Uncle Sam,” I said, “Thanks, but I don’t have an uncle named Sam.” Of course, they sent me another one. My experience, going into the service, although I had been in the South, I was very carefully guarded. During the Christmas season, we would have games with Black high schools in the South, Oklahoma City, Memphis, D.C., whatever. People knew we didn’t know what we were doing so they would protect us. When I went south after I was drafted, it was the first time that I was confronted, though I lived in a segregated neighborhood and all, with the blatantness of segregation. And my father’s spirit came up again. But when I was confronted overseas by Europeans who asked, we see Negro troops under white officers, but we never see white troops under Negro officers, my American spirit came up, “Ain’t none of your goddamn business.” We were going to straighten that out though when we get back home. There were many who felt that way, white and Black, and particularly Jewish people. Because there was a great deal of anti-Semitism still boiling.

The Depression had its effect and, because being African American people in Europe, even our so-called allies, we saw that division and wondered why that division existed, because we thought we were just as smart as the Caucasians, which we were, and, at times, even smarter. I came home with an honorable discharge.

BD: You remember places like the Regal during the heyday of 47th Street?

I remember when the Regal and Savoy were built. We used to live right down the street. We went to the “Met” [Metropolitan Apostolic Community Church] first. We just began to move into the neighborhood after the 1919 riot, Blacks began to move south and concentrate around 31st Street. The Vendome, where I first saw Louis Armstrong when I was about four or five years old, that talent began to come south from 31st and 35th, to 47th Street, and 47th Street became the jazz street. One of the hangouts was the “The Palm Tavern” which became known as “Gerri’s Palm Tavern” because between breaks all those guys would get together. It was a magnificent street from Michigan to Cottage Grove, it was full of life.

BD: Most of those buildings are gone now. The old Rosenwald apartments are still there.

Yes, the Rosenwald’s still there and we’re still trying to save it. Along with his grandson, we’re still trying to save the Rosenwald. It’s not so much the architecture of the Rosenwald, it’s who was there. All those people that you’re mentioning, they had friends who lived in the Rosenwald, they were not poor people by any means. Most of the people at the Rosenwald moved over here. You see those big mansions and those greystones brownstoners around there where Mr. Barack comes every once in a while. Those are the kind of places they bought when the left the Rosenwald. But Rosenwald was, among the swanky, it was the swankiest in those days. Because I was versatile, I had friends, and I had a lot of good times there. That didn’t break after World War II, and after the Hansberry decision. That’s a physical example of the Blacks that fled poor neighborhoods, and again the competition was moving to Hyde Park.

A lot of musicians, I don’t know if they lived there, but they spent time there, but the artists, because when they built the Rosenwald, they also built the George Cleveland Hall Brach Library. Mr. Rosenwald owned both the lands there and donated the land to the city, but he built the Rosenwald. Now one of the grandchildren of the first manager of the Rosenwald is now very close to the President of the United States, Valerie Jarrett. Her grandfather was the first manager, Robert Taylor. Mrs. Bowman and Dr. Bowman, the Bowmans, were the mother and father of Valerie. That’s just a sample, in a sense, of carrying that two generations or three generations forward, of the kind of African Americans that the president has around him, they are very confident academically, but experientially they have not been out there in the streets, because mom and daddy wouldn’t have it. I was the same way, particularly after my children’s mother and I separated. I was very protective. You can guess at it, but you never experience it or see it because you’ve been denied the opportunity.

Mr. Taylor was a good friend of Rosenwald’s. He had the responsibility for the design of another public housing way before Taylor housing projects. He didn’t want those houses. I tried to tell Barbara and her sister, take your daddy’s name off those places, it’s a disgrace. The Ida B. Wells projects, which were very similar, but with the Ida B. Wells you had to be low income, but temporarily. Save a little money and move. The Ida B. Wells and the low-rise housing projects in Chicago were built as public housing, and that was to be the younger people who were starting families, come in and move out. And that was true for the housing they just tore down the last building on the west side, that was built for lower class or lower income Italians. The other one on the west side was built for immigrant Jewish people. When the influx of these newcomers came, they moved into there and then they had to build high-rises because there were so many of them and they wanted to control those. And that became the base of the Daley regime.

They then had Black politicians who were here, I don’t want to defame them at all, almost like my adopted son’s father, Metcalfe, who could then help organize those places and the outside would not be accused of being racial. Because Ralph Metcalfe and all those were Negroes. They can now move into the upper echelon income level and do quite well. Until Daley and them removed the base of their power, and took away the patronage system so that the ward committeemen or aldermen couldn’t dictate who would get the jobs and the awards, they had to come straight to the mayor to get those favors.

There’s another thing. You can get old, but you don’t have to act old. That is my point. Ish was like that. Margaret was like that. They continued to be active almost until the day of their deaths. You feel fulfilled. You wake up one day and say, oh boy! I used to be thirty-five, I used to be twenty. Time passes because you have something worthwhile that you’re trying to do, whatever it may be. But you’re trying to do something that goes beyond you. You hit a certain level, you’re going to make enough money to take care of food, pay your rent, or buy a house. What can you say that you gave beyond that. That’s where the fulfillment, for me at least, and I think that’s the reason Margaret, almost all of those people that you’ve been referring to, they lived full lives, to the greatest extent of their ability. Once they were ill, they didn’t live very long. They didn’t want to. They had their fun.

On the last day of Kindergarten, I got a big hug from my six-year-old, Jake. Before he was born, one of my mentors, Antonia Darder, a critical pedagogy scholar, told me that having children gives you a new reason to do social justice work. I didn’t understand at the time, but her words have come back to me. It’s because of my own kid that I have been writing about families separated by Trump’s anti-immigrant policies.

On the last day of Kindergarten, I got a big hug from my six-year-old, Jake. Before he was born, one of my mentors, Antonia Darder, a critical pedagogy scholar, told me that having children gives you a new reason to do social justice work. I didn’t understand at the time, but her words have come back to me. It’s because of my own kid that I have been writing about families separated by Trump’s anti-immigrant policies. Diego’s father is now back home, but federal authorities are moving fast with what they call “removal proceedings.” I plan to write about the father’s arrest, but I have been working to confirm his story, and get permission from the family. There are revelations about Sheriff Dan Walsh’s cooperation with ICE that I cannot yet fully disclose. Families don’t just deserve to be together, but they should have the right to be free, to move, to work, to remain free from state surveillance and criminalization.

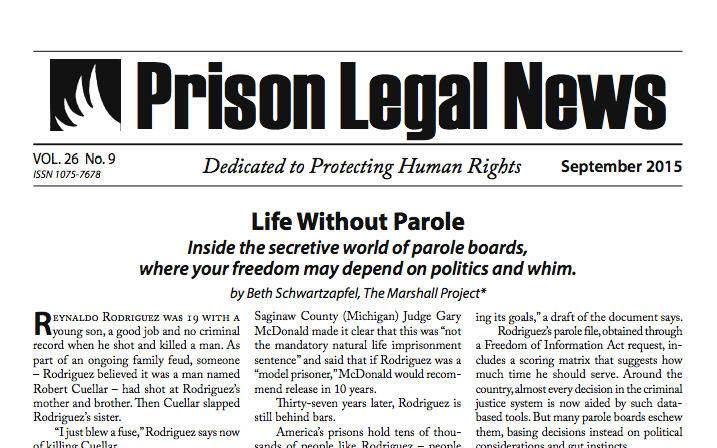

Diego’s father is now back home, but federal authorities are moving fast with what they call “removal proceedings.” I plan to write about the father’s arrest, but I have been working to confirm his story, and get permission from the family. There are revelations about Sheriff Dan Walsh’s cooperation with ICE that I cannot yet fully disclose. Families don’t just deserve to be together, but they should have the right to be free, to move, to work, to remain free from state surveillance and criminalization. I also continue to write about families impacted by mass incarceration in the United States. I sat with Black youth at a forum, “Challenging Electronic Monitoring in Cook County,” at the University of Chicago put on by my friend and comrade James Kilgore.

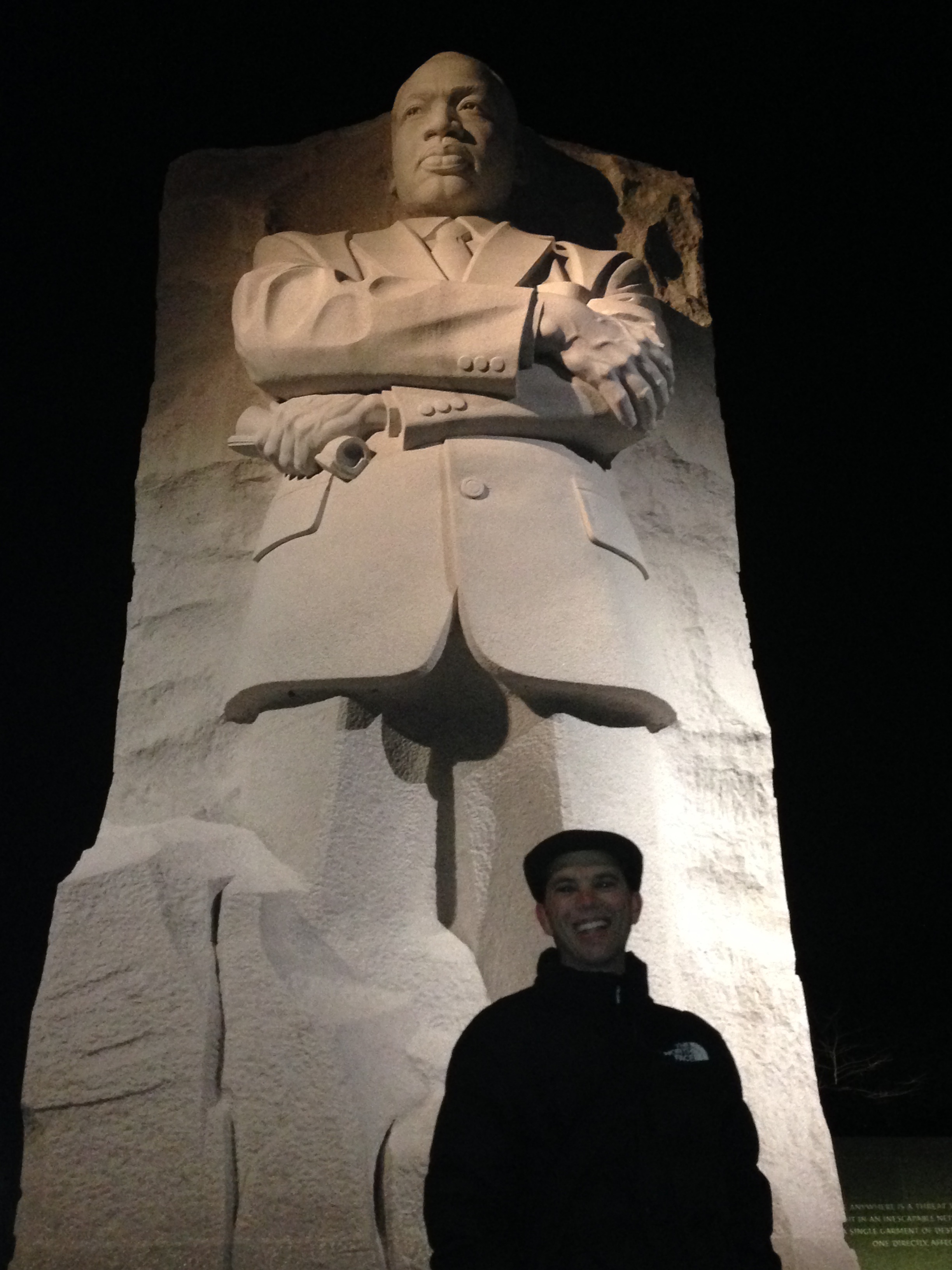

I also continue to write about families impacted by mass incarceration in the United States. I sat with Black youth at a forum, “Challenging Electronic Monitoring in Cook County,” at the University of Chicago put on by my friend and comrade James Kilgore.  This summer I went to see an exhibit of Charles White, African American artist of the Black Chicago Renaissance, whose work graces the cover of my book The Negro in Illinois. I got a personal tour by John Murphy who helped curate the show currently up at the Art Institute of Chicago. Earlier this year we were on a panel at the annual conference of the College Language Association.

This summer I went to see an exhibit of Charles White, African American artist of the Black Chicago Renaissance, whose work graces the cover of my book The Negro in Illinois. I got a personal tour by John Murphy who helped curate the show currently up at the Art Institute of Chicago. Earlier this year we were on a panel at the annual conference of the College Language Association. My job as a full-time activist at the IMC has been a reminder that we must not only work for our own freedom, but that we must empower others to find their own vision of liberation. I have seen other activist friends burn out, become famous, have babies, face emotional breakdowns, and overcome health crises. When we falter, are there others to help carry the load? How do we pave a path for others to tread? How do we get there together? How do we build our own collective power?

My job as a full-time activist at the IMC has been a reminder that we must not only work for our own freedom, but that we must empower others to find their own vision of liberation. I have seen other activist friends burn out, become famous, have babies, face emotional breakdowns, and overcome health crises. When we falter, are there others to help carry the load? How do we pave a path for others to tread? How do we get there together? How do we build our own collective power?